The inquiry is led by a chairperson, often a senior judge or legal expert, who oversees the process.

Public inquiries are major investigations commissioned by a government minister when there is a ‘public concern’ about a particular event or set of events. This can be following huge disasters, such as the Grenfell Tower fire, major miscarriages of justice, such as the Post Office Horizon IT scandal, or more discrete topics, such as the death of Dawn Sturgess from the Novichok poisoning in Salisbury in 2018.

In this guide, we indicate who participates in a public inquiry and highlight the difference between statutory and non-statutory public inquiries. We also set out the inquiry process in detail and advise when it’s appropriate to instruct legal support.

Regardless of the focus, the goal of all public inquiries is generally threefold:

In establishing these questions accountability is often found, and conclusions of findings a recorded in a final report.

The inquiry is led by a chairperson, often a senior judge or legal expert, who oversees the process.

In some inquiries, the chairperson is assisted by a panel of experts with knowledge in relevant areas to help assess the evidence and assist the chair in reaching conclusions.

These are individuals or organisations directly involved or affected by the subject of the inquiry. Core participants have a special status, allowing them to give evidence, make legal submissions, and access relevant documents. Examples include victims, families, government bodies, or businesses.

A legal team appointed to help gather evidence, question witnesses, and assist the chairperson in the legal and procedural aspects of the inquiry.

These can be individuals who have firsthand knowledge or experience related to the events being investigated. They may be requested to give written and/or oral evidence during the inquiry.

Lawyers representing core participants, witnesses, or other interested parties. The legal representatives of core participants may make submissions, question witnesses and make legal arguments on behalf of their clients.

Specialists in relevant fields, e.g. forensic, medical, or technical experts, who provide independent expertise to help the inquiry understand complex issues.

A support team managing the logistics and administration of the inquiry, ensuring it runs smoothly.

Public inquiries can be statutory or non-statutory. A statutory inquiry is governed by the Inquiries Act 2005 and Inquiry Rules 2006, and gives the chair a suite of powers and uniform procedures aimed at uncovering evidence for the public record. This includes compelling witnesses to provide relevant documents and provide testimony in person, or through a witness statement. A failure to comply without a reasonable excuse constitutes a criminal offence, punishable by a fine or imprisonment.

In a statutory inquiry, the chair must also take reasonable measures to ensure public access to the proceedings and information, potentially allowing public attendance, live broadcasting of hearings and online publication of relevant documents. In recent Inquiries, evidence has been live streamed on platforms such as YouTube.

Non-statutory inquiries are not governed by an Act of Parliament or any procedural rules. They can be conducted either privately or publicly and witnesses cannot be forced to attend or produce relevant documentation during the process - instead they rely on voluntary cooperation. In some cases, non-statutory inquiries can be converted to statutory if deemed necessary.

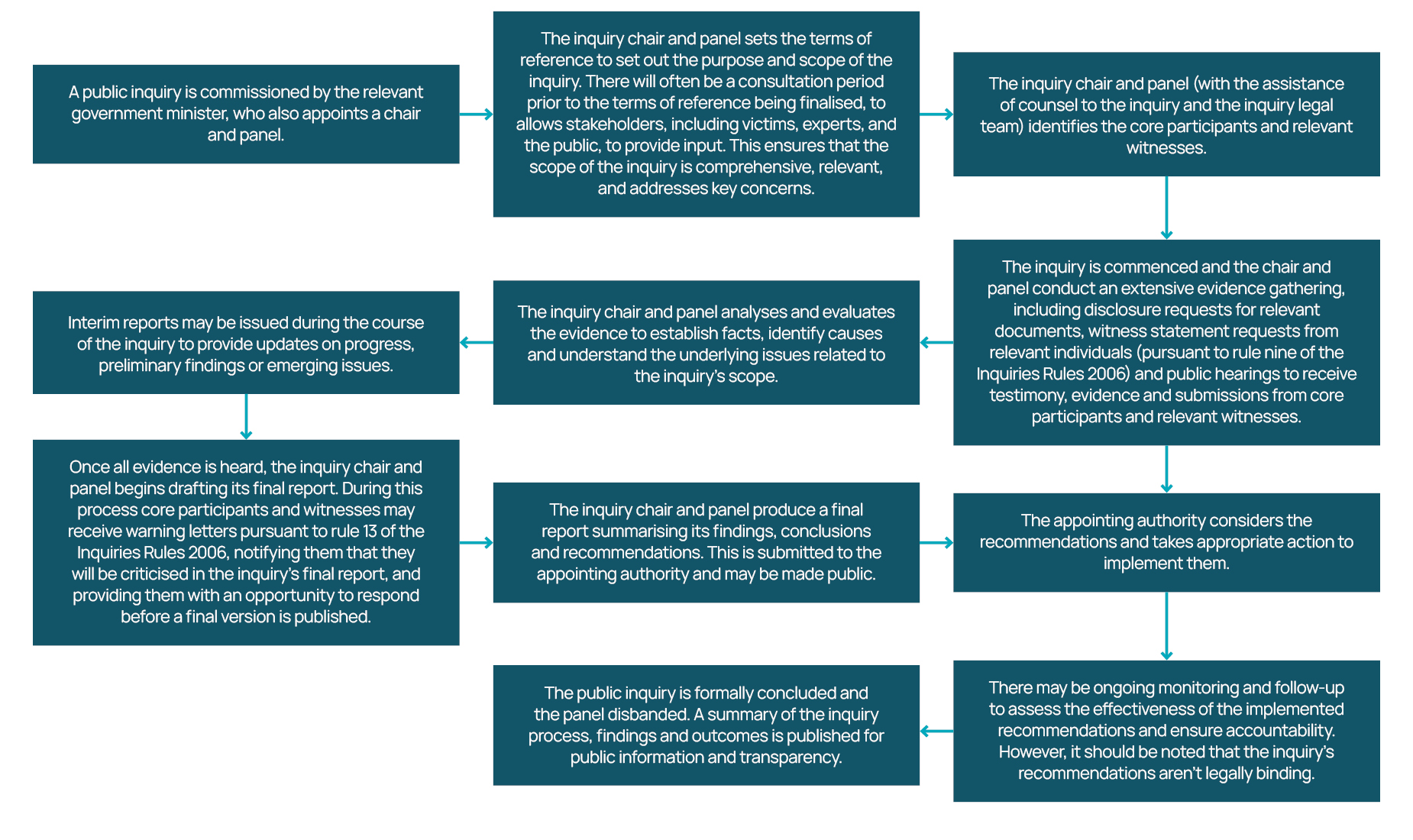

Below is a flow chart providing an overview of how a statutory public inquiry runs.

While inquiries are inquisitorial rather than adversarial and all participants are there to support the inquiry in establishing the matters subject to the terms of reference, in practice, questioning of witnesses can commonly be heated and can bear close resemblance to cross-examination. Whilst the public interest demands that searching questions be asked of witnesses and assertions of accountability can be made, the process doesn’t exist to establish criminal or civil liability against an organisation or individual.

Public inquiries don’t exist in isolation. There will often be other proceedings or investigations, such as by the police or by regulator such as the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Care Quality Commission (CQC) or Environment Agency, or investigations by professional bodies, conducted in tandem. These proceedings will often await the outcome of the public inquiry. Findings of accountability during a public inquiry may influence other investigatory bodies to take further legal or civil action against the parties involved.

There is also the possibility of group litigation from those affected by events. During an inquiry, standstill agreements are often entered into to prevent litigation from going forward until the findings are published, at which time lawyers can take the case forwards.

One challenge that can emerge during a public inquiry is the risk of self-incrimination. This is especially relevant where is it clear that an individual is likely to be subject to investigation which may lead to criminal prosecution. This concern can lead to hesitation in providing open and honest evidence, which can reduce the inquiry's overall effectiveness.

To address this, the law governing statutory inquiries requires the chair to inform witnesses that they aren’t obligated to answer questions if they believe doing so could incriminate them. This is commonly known as a ‘rule 22 warning’ pursuant to section 22 of the Inquires Act 2005.

Another potential solution to ensure open and honest evidence is provided, is for the chair to request assurances from the attorney general or the director of public prosecutions in England and Wales, ensuring that the evidence provided by witnesses will not be used against them in future legal proceedings. This doesn’t prevent civil or criminal actions from being taken, but it guarantees that their own testimony will not be used as evidence.

If you’ve been appointed as a core participant in a public inquiry, or have received a request to provide witness evidence, engaging legal support from the outset is crucial. Being legally represented will ensure that you fully understand your rights and obligations and can help you navigate the complexities of the inquiry process, reducing the overall burden on an individual or organisation.

The work involved with providing submissions, disclosure and preparing for and attending public hearings can be lengthy and complex. For witnesses requested to give evidence, this often requires detailed analysis and review of voluminous disclosure, as well as careful consideration of lengthy sets of questions to produce a comprehensive witness statement.

The right legal support will assist you in your preparation and participation during the inquiry by providing practical support in organising and interpreting information and guiding you on how to participate effectively. Witnesses can benefit from support in the preparation of written statements and giving oral evidence.

At Ashfords we have a team of dedicated regulatory solicitors with a wealth of experiencing in supporting core participants and witnesses in public inquiries. If you require legal advice or wish to be supported through an inquiry process, please contact our regulatory team below

Contact the team