In September 2023, I wrote about a legal claim then proceeding through the English Court system, brought by Thatchers Cider Company against Aldi Stores.

I explained how, in the UK, brand owners have increasingly come to see supermarkets, and in particular the German discounter Aldi, market and sell competing supermarket own brand products, bearing labelling and packaging which (at the very least) ‘winks at’ (if not intentionally mimics) the appearance of brand owners’ products. Successful attempts to prevent such activity have been rare, but I wondered whether such pernicious behaviour might be about to end if Thatchers succeeded in its claim against Aldi.

On 24 January 2024, the first instance Court’s judgment was handed down. What lessons can we learn from it?

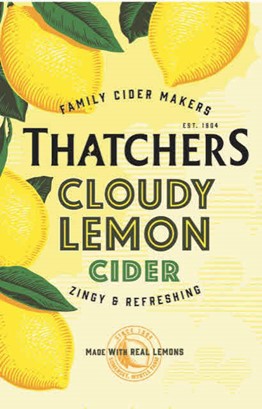

Since February 2020, Thatchers have sold in the UK a cloudy lemon cider product with the following packaging design, which it has registered as a UK trade mark:

Thatchers claim the product has been highly successful, such that the packaging (and hence the registered trade for the packaging) has acquired a reputation in the UK.

Thatchers object to the appearance and sale by Aldi, since 2022, of the following cloudy lemon cider:

Thatchers claim the overall appearance of the Aldi product is highly similar to that of the Thatchers product sold under the registered trade mark and that it is far more similar in appearance than other third party cloudy lemon products on the UK market. Further, in adopting the appearance of the Aldi product, Aldi intentionally set out to cause a link in the minds of consumers between the Aldi product and the Thatchers product, in order to encourage customers to buy the Aldi products and thereby benefit from that link.

Thatchers assert that what Aldi has done is, inter alia, contrary to s.10(3) of the Trade Mark Act 1994. Pursuant to s.10(3) of the Trade Mark Act 1994, a person can infringe a registered trade mark if they use, in the course of trade, in relation to goods or services, a sign which is identical with or similar to a registered trade mark, where the trade mark has a reputation in the United Kingdom and the use of the sign, being without due cause, takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trade mark.

No misrepresentation or likelihood of confusion is necessary to succeed with a s10(3) infringement claim. In other words, consumers do not need to be confused into thinking that the Aldi product is the Thatchers product, or that Thatchers is in some way involved in its production.

Amongst other things, Thatchers allege that the appearance of the Aldi product ‘free-rides’ off the reputation of Thatchers registered trade mark, in order to benefit from its power of attraction, fame and/or prestige, exploiting the marketing effort expended by Thatchers and transferring the image of the Thatchers cider product and registered trade mark to the Aldi product and its appearance. In other words, the similarity in appearance is intended by Aldi to make its product more attractive to consumers, so as to influence their economic behaviour away from the Thatchers product and towards the Aldi product.

The Court held that Aldi used Thatchers product packaging as a benchmark for the packaging of its own product.

It also held that Thatchers registered trade mark had a reputation throughout the UK and, due to the extensive nationwide use that Thatchers had made of it, the mark had enhanced distinctiveness. Furthermore, Aldi’s packaging called to mind Thatchers registered trade mark.

Despite these factors, the Court concluded that, primarily due to the overall appearance of the Aldi product being only similar to Thatchers’ registered trade mark to a low degree (in particular, due to the dissimilar brand names THATCHERS and TAURUS), Aldi’s packaging did not ‘free-ride’ off the reputation of Thatchers registered trade mark.

The judgment is not the game changer it was hoped by some it might be. It will not encourage others to bring cases against supermarket ‘look-a-likes.’

If the decision is appealed successfully (and from reading the judgment there appear to be possible grounds to do so) then obviously that would change matters. Time will tell.

Despite Thatchers’ case failing, brand owners should still look to register the visual appearance of the packaging of their goods as registered trade marks and then to pursue infringement proceedings (pursuant to s.10(3) of the Trade Mark Act 1994) against supermarkets (or others) who decide to produce ‘unnecessarily similar’ looking packaged goods. The key is to make sure that the evidence presented before the Court convinces it that free-riding is taking place. Had Thatchers presented evidence to show that consumers are influenced in their purchasing decisions as much by the colour and overall design and appearance of a product’s packaging, as they are by the brand name of the product, then perhaps they might have succeeded at first instance.

For more information please contact Clare Jackman.

We produce a range of insights and publications to help keep our clients up-to-date with legal and sector developments.

Sign up